Warp and Weft, Amber Butchart, World of Interiors, 5 October 2023

https://www.worldofinteriors.com/story/the-fabric-of-democracy-propaganda-textiles

Warp and Weft

A new exhibition at London’s Fashion and Textile Museum looks at the ideological positions communicated by the most innocuous-seeming of domestic fabrics. It’s a stitch-up, says its curator

By Amber Butchart, 5 October 2023

In 1928, a catalogue for a Soviet exhibition on Textiles for Daily Life noted that its subjects were ‘ideological goods’ that could have a sizeable impact on society. We don’t often consider fabrics to be political objects, but, just like monumental artworks or propaganda posters, they have often been used to transmit ideological messages.

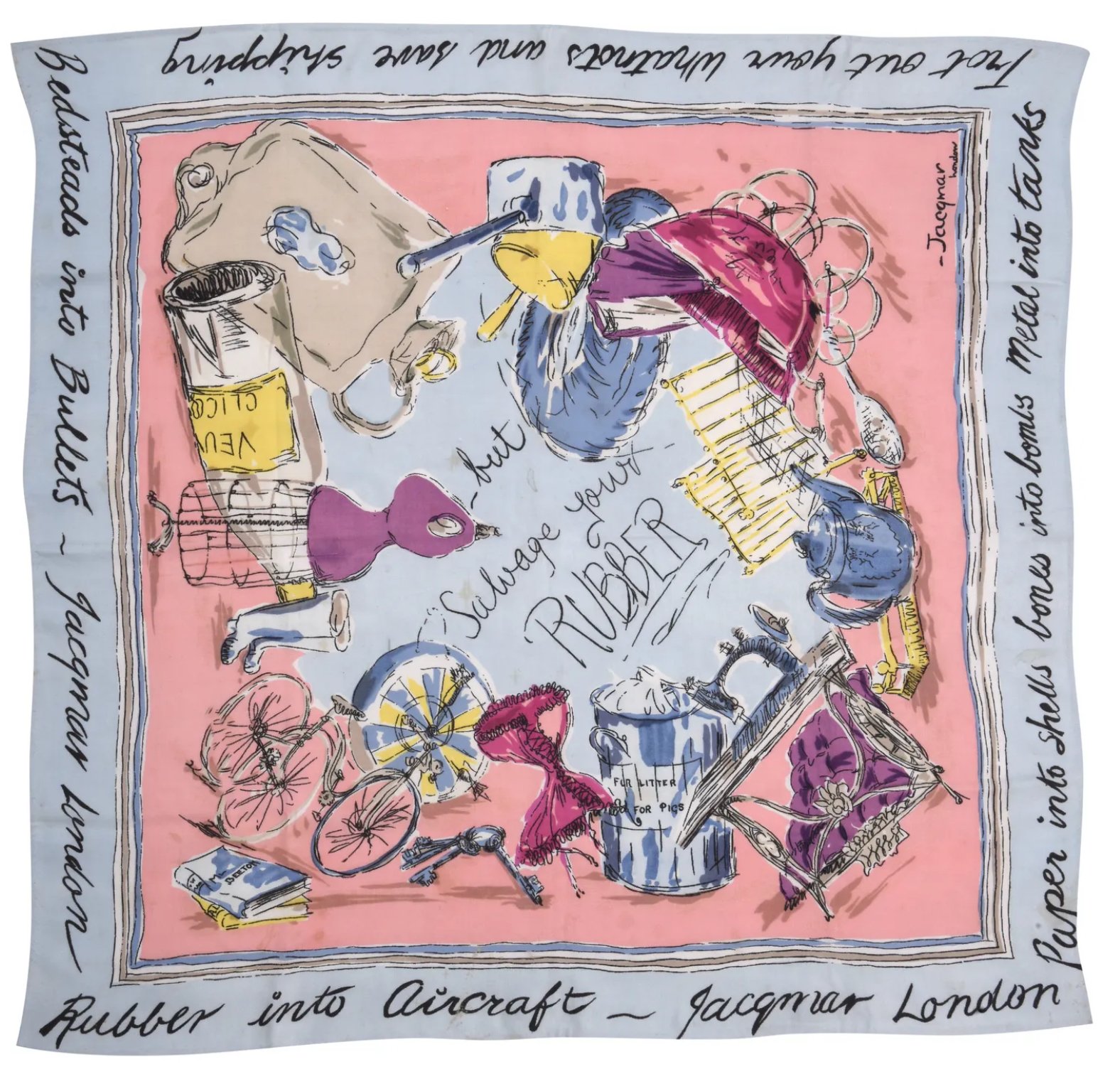

Just as the printing press revolutionised the spread of information in 15th-century Europe, the development of various techniques for printing on fabric made it easier to circulate messages on cloth from the mid-18th century onwards. Industrial methods built on earlier knowledge from Asia of printing, dyeing and mordants to expand the manufacturing of textiles. These increasingly affordable processes also ‘democratised’ their decoration, allowing governments and corporations to harness the power of print to communicate, be they wartime slogans or revolutionary ideals.

Revolutions require simple messages, and many regimes have sought to extend this into daily life to solidify their grip on power. In the newly established Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Constructivists sought to replace capitalism with a state-owned means of production to create mass-produced ‘socialist objects’, extending radical fervour to everyday life and work. Printed cottons, manufactured in Russia since the 19th century, were seen as an ideal example of this process, and could be used to transmit the goals of the new state and raise political consciousness.

After the 1949 Communist Revolution in China, textile factories were nationalised and placed under state control. In the early 1950s, designers at the Shanghai Eastern China Bureau for Textiles developed designs that evolved from traditional celebratory imagery, and they were also inspired by large-scale floral fabrics imported from the Soviet Union. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), a period of great violence, censorship and destruction, auspicious motifs such as landscapes, flowers and birds were combined with revolutionary symbols of progress, including factory chimneys and scientific paraphernalia. They were produced primarily as quilt covers, affordable decorative items that signified a new industrial self-sufficiency. Imagery might be borrowed from propaganda posters to create politically acceptable motifs for the home.

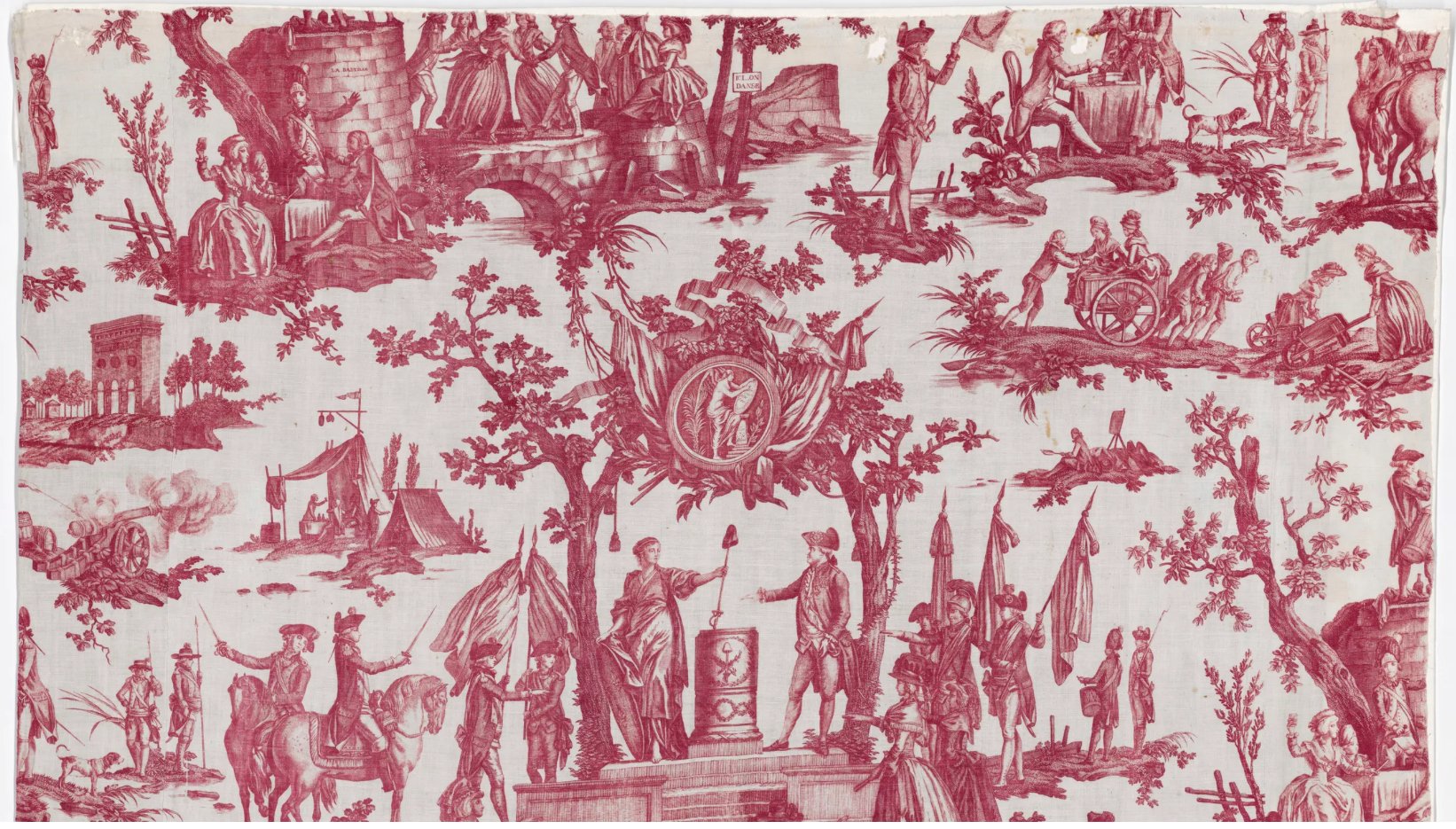

In 1760, Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf set up a workshop in Jouy-en-Josas, near Versailles. The following decade he began using a new copperplate method that had been developed in Ireland from engraving techniques used for paper. He created the most famous versions of what became known as toile de Jouy, specialising in highly detailed pastoral scenes.

We still associate this style with traditional Gallic design and assume it is ‘just’ decorative and entirely apolitical. But examples created around the time of the French Revolution tell a different story. One celebrates the Fête de la Fédération of 1790, which commemorated the revolutionary events of the previous year. Louis XVI is depicted taking the oath of the federation, facing Liberty and brandishing a Phrygian cap, a symbol of the revolutionary cause. Other members of the royal family, including Marie-Antoinette, also feature. This peaceful moment was short-lived, as both the king and queen were executed by guillotine in 1793.

In more recent years, exhibitions and festivals have been used to foster civic pride on a global stage, celebrating inventions and manufacturing prowess. The 1951 Festival of Britain opened against the backdrop of postwar austerity, and was advertised as a ‘Tonic for the Nation’. Designs were produced by the Festival Pattern Group using Helen Megaw’s pioneering work into x-ray crystallography, and adorned products ranging from carpets to soft furnishings, porcelain and glassware. These motifs, with their optimistic aestheticisation of science, are a very literal example of atomic design. They show how Britain was constructing a new postwar identity, defining itself through ideas of progress and modernity using mass-produced items for the home.

During this period, the Cold War saw tensions between capitalism and communism reach a zenith. While the usual narratives of this period focus on the space race and nuclear arms, these ideas permeated the home too. This was evident in 1959 in an incident that became known as the ‘Kitchen Debate’. At the opening ceremony of the American National Exhibition in Moscow, US vice-president Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev each argued their case in a heated discussion that took place in a model kitchen: evidence that everyday domestic life could become a political battleground.

Propaganda may have 20th-century connotations, reminiscent of a time of grand narratives and competing economic ideologies. But it is still very much alive in the 21st century, when information in the public realm is increasingly contested and democracy itself is wearing thin. The divisive populism of recent years is evidenced by a ‘Got Brexit Done’ tea towel that was, for a brief period, official Conservative Party merchandise. Featuring the then prime minister, Boris Johnson, surrounded by floral emblems of all four UK nations in a false show of unity, the design deftly ignored the fact that Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU. Cheaply printed and sold for £12, it’s remarkable that such an innocuous object, a humble domestic cloth, can speak so confidently of our present time.

‘The Fabric of Democracy: Propaganda Textiles from the French Revolution to Brexit’ runs at the Fashion and Textile Museum, 83 Bermondsey St, London SE1, until 3 March 2024